Posts

Showing posts from 2019

The Lady Hardcastle Mysteries by T.E. Kinsey

- Get link

- Other Apps

A Conformable Wife by Alice Chetwynd Ley

- Get link

- Other Apps

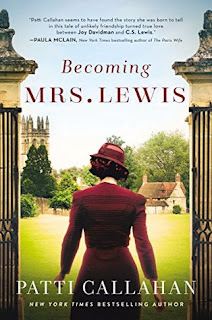

Becoming Mrs Lewis by Patti Callahan

- Get link

- Other Apps

Thunder On The Right by Mary Stewart

- Get link

- Other Apps